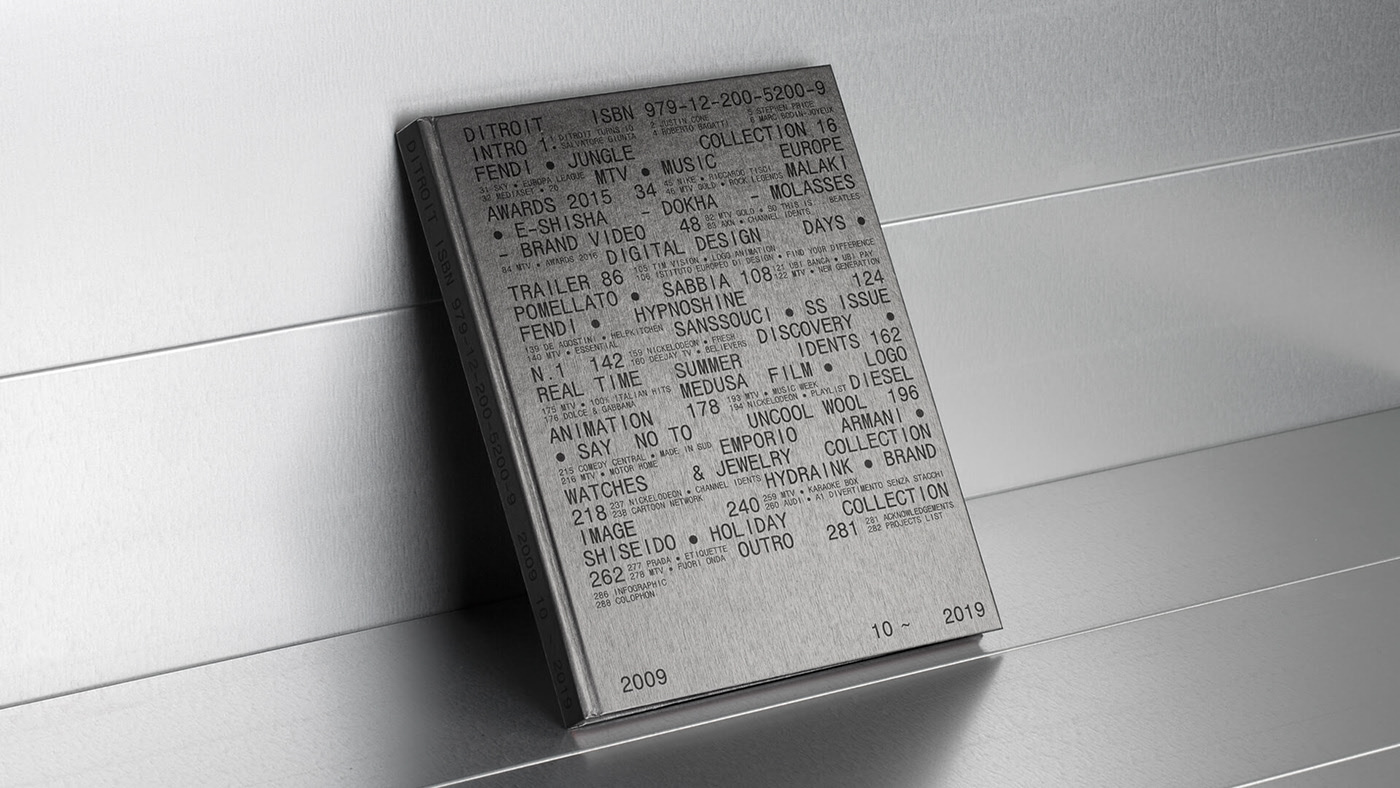

The following interview originally appeared in a book celebrating Ditroit's 10th anniversary.

What kind of evolution have you noticed in motion design in the past 10 years?

Over the last 10 years, a number of developments in both the aesthetics and business of motion design have radically altered what it even means to be a motion designer. Viewed from one angle, the field is flourishing and diversifying like branches on a magical tree, with each limb bearing delicious, new fruit. Viewed from another angle, motion design is all but dead. In its place is a fractured collection of practices working in the service of new masters. How you see it depends on your point of view.

First up: aesthetics

First, let’s discuss aesthetics. The last decade saw the rise—and peak, I would argue—of 2D animation in motion graphics. In the early 2000s, an obsession with cutting edge CG techniques gripped the field. It seemed everyone was either trying to reproduce the glassy broadcast graphics they grew up with on television or subvert those conventions by bending CG applications toward more experimental ends.

As CG became more accessible, both in terms of cost and ease of learning, motion designers’ love affair with CG cooled. Novel workflows around vector graphics gained popularity and a newfound fascination with traditional cel animation fueled an obsession with 2D animation in motion graphics. This blurred the lines between character-based animation and motion graphics, turning up the volume on the perennial question, “What exactly is motion design?”

(Some even question whether motion design still exists as a field, preferring instead to label everything as simply “animation.” This has sparked a minor identity crisis for a few practitioners.)

CG’s triumphant return?

There are signs, however, that CG is making a comeback. A new breed of GPU-accelerated renderers is changing the way designers work in CG. Artists who previously shied away from CG are now tempted to try new things, spawning interesting hybrid aesthetics and workflows that blend the expressiveness of 2D with the endless possibilities of CG.

Meanwhile, the business of motion design has changed radically over the last decade. The rise of streaming content providers like Netflix and Amazon has dealt devastating blows to legacy broadcast content providers. This has dried up much of the high-paying work in promos and advertising that once kept motion designers well-fed. On the flip-side, streaming shows have motion design needs of their own. But the budgets are often smaller, despite rising client expectations. In short, it’s tough out there.

Big tech’s influence

Big tech companies have also altered the business landscape as they’ve spent the last 10 years attempting to build in-house teams with capabilities that can compete with external studios. This has not only put financial pressure on small and mid-sized studios, it has meant that many senior motion designers have left the freelance market for full-time jobs that come with perks like premium healthcare and retirement savings plans.

At the same time, there has been a flood of junior talent entering the marketplace, due in part to the prevalence of well-produced online learning programs that promise to train anyone in the basics of motion design for a fraction of traditional art school prices. The success of these programs has paradoxically meant that it can be harder for junior talent to find meaningful job opportunities, as employers are surrounded by options for new talent.

Another unintended consequence of these new learning platforms is the perceived commodification of motion design. Fueled by the never-ending need for disposable content on social media, some clients unfortunately see motion design as a low-cost necessity that can be filled by virtually anyone, provided the output meets a low baseline of quality and brand standards. Junior talent, hungry for work, are all too willing to fill this need, driving down the overall perceived value of motion design.

Incidentally, this is a challenge that the field of graphic design has been struggling with since the inception of desktop publishing in the early 1990s. The shadow of democratization is commodification. While it can feel like the beginning of the end for senior artists, it needn’t be. Motion design is simply finding its way through adolescence. The field is already in the process of maturing, of learning how to think more strategically and position itself as a vital component of business rather than as simply an exciting creative field (which it still is, in my opinion).

Why did you feel the need to start a project like Motionographer?

Back in the early 2000s, I was working for a university when a friend of mine introduced me to an amazing internet forum called mograph.net. There, I found links to dozens of 320x240 pixel videos (cutting edge back then) created by companies I had never heard of, places with weird names like EyeballNYC, MK12, Lobo and Psyop.

I wanted to collect all the amazing things I found and keep track of the studios I liked the most. So, being a web developer, I built a blog called Tween. I started posting my favorite projects and occasionally added commentary, even though I had no idea what I was talking about. The site’s traffic quickly grew, and I invited collaborators to post their favorite work, too.

In 2006, when I started graduate school at the Savannah College of Art and Design, I took the opportunity to re-imagine Tween as a slightly more grown-up site, which we decided to call Motionographer. I increased the amount of time I spent posting work, invited more collaborators on board, and our traffic swelled. By 2009, we were garnering over 1 million pageviews a month.

In today’s market where there is so much information saturation, and technology and media are so accessible, how can you build a project that can stand out among the crowd?

This may not be a popular opinion, but the work that stands out is not the work that entirely ignores the trends of the day. Trends are important, despite what some designers may say about them. Trends are co-creations of artist and consumer, and as such they are valuable conventions that can enable frictionless connection between audiences and creators.

Work that stands out—and is celebrated and shared—is work that expands the edges of a trend or combines multiple trends in a novel way. When trends are completely ignored, the viewer often feels disenfranchised, cut out of the inherently participatory nature of viewing a project. They feel abandoned.

Instead, try disrupting the system from within. You have a much greater chance of being noticed if you acknowledge that you, like the viewer, are part of a dynamic cultural landscape. Invite the viewer to pervert it or subvert it rather than act as though it doesn’t exist.

What do you think of the European scene versus the US one? Which one do you think Ditroit fits the most into?

This is a massive oversimplification, but I’ve always felt that the European scene is more conceptual than the US scene. In general, it seems that European studios (and audiences) are more comfortable with abstraction, minimalism and visual metaphor than US audiences.

I think this claim is clearly exemplified by Ditroit’s work, which is highly conceptual. Ditroit’s projects invite the viewer to make connections between the visuals and the brand in unexpected ways. The viewer needs to work a little to “get” it, and that is (in my opinion as someone from the US) a very European approach.

Are there any downsides to becoming a professional motion designer?

Motion design sits at the intersection of many disciplines, including graphic design, animation, filmmaking, visual effects, sound design and music composition. It makes sense, then, that motion designers are interested in all these things and more. Motion design is a profession which tempts its practitioners to master many fields.

Unfortunately, that sort of mastery is impossible. It would take a lifetime to master just one of the fields involved in motion design. So the biggest downside to being a motion designer is the intense frustration one feels in never having truly mastered their craft. When you approach proficiency in one area, you realize that you have drifted away from excellence in others.

This endless pursuit for confidence in multiple disciplines is linked to another downside of being a professional motion designer: long hours.